Oliver Cossairt loves to destroy famous works of art — at least digitally. He’s an assistant professor of electrical engineering and computer science at Northwestern University with a love of art and an urge to understand how it’s made. How that perfect shadow ended up on the canvas. How that one brush stroke completed the story.

But rather than spend decades mastering his technique and chasing the masters one painting at a time, Cossairt attacked the problem in the way he knows best: with math. He and his team developed an equation that can lift colors from the canvas to “peel back the paintings.” Layer by layer. Brush stroke by brush stroke. All in the hopes of discovering precisely how artists created their paintings. And it answers one huge, longstanding historical question: how these artists’ methods evolved over time.

“A lot of what I do is imaging techniques for scientific purposes,” Cossairt says. “[I was] asked if there was any way to apply imaging techniques that I work on to art analysis techniques useful for art conservators at The Art Institute of Chicago.”

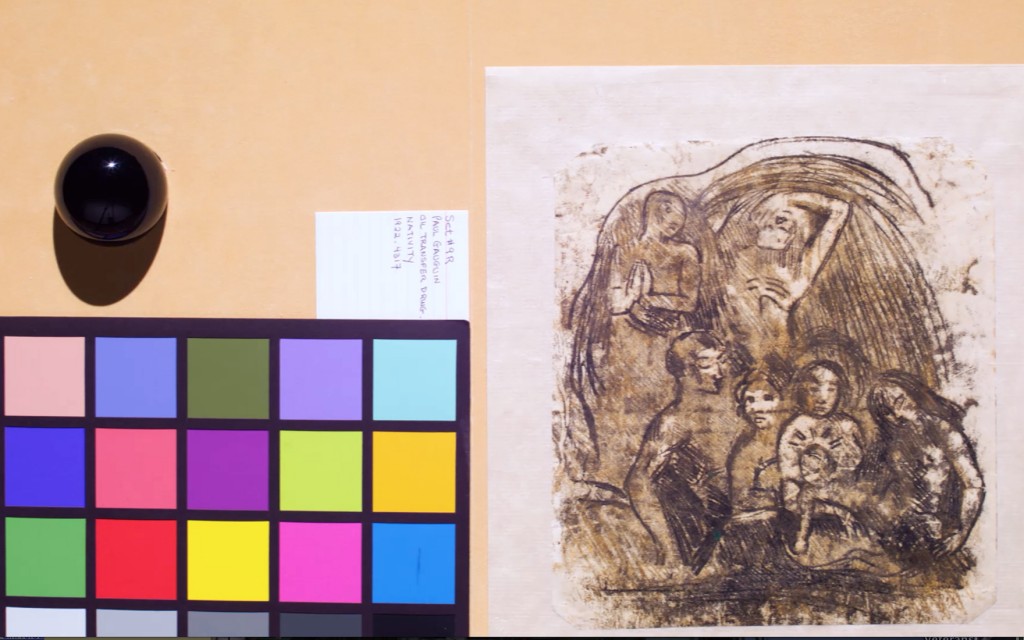

The answer: Heck yeah. Cossairt came up with the idea of using the “photometric stereo” technique to see the works of art — in this case, Paul Gauguin’s 1902 print “Nativity (Mother and Child Surrounded by Five Figures)” — in ways they never have been before. The whole process starts by creating a 3-D image of a painting or print. Doing that requires snapping multiple pictures of it. First, Cossairt and his team set up a light at a precise angle. They snap a picture, then slightly move the light to another angle. Click. Repeat — until they’ve covered the entire piece. They compile the photos digitally. Then — and here’s the odd part — the color is removed. But without all that color in the way, the real surface is revealed: the hidden divots and slopes at a microscopic level.

“This is the equivalent of removing make-up from a face,” says Marc Walton, research associate professor of materials science and engineering at Northwestern. “The make-up, or color, masks the underlying structure of the skin, which may contain wrinkles, spots, etc. Same thing with paint on a canvas. The dimensionality of the paint is often obscured by the color.”

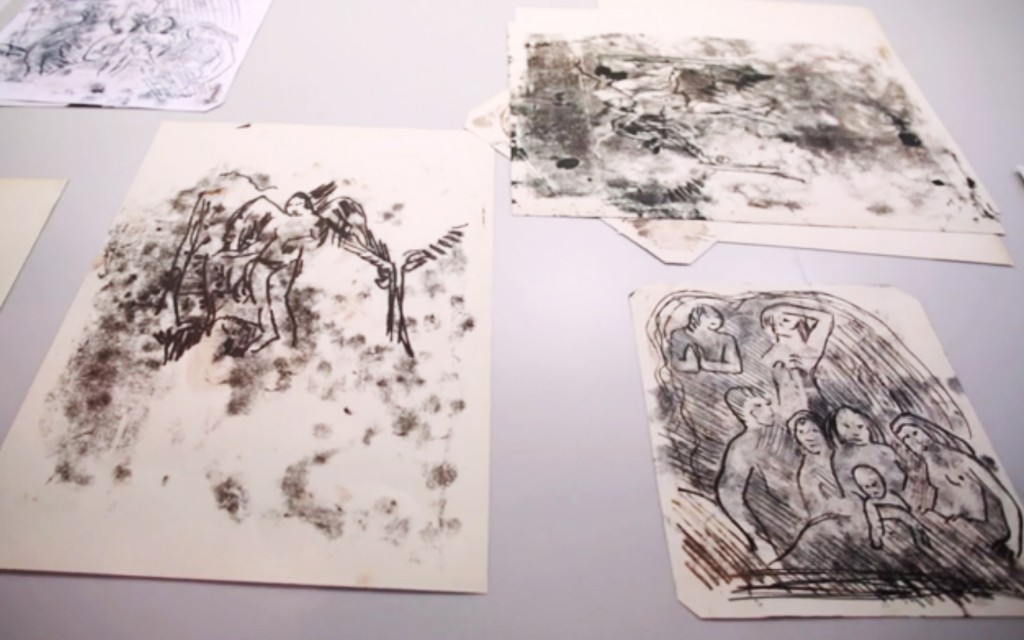

And that dimensionality can help academics and art historians figure out things they never thought possible. Take Gauguin’s “Nativity” for example. Historians knew the French Post-Impressionist’s methods involved transferring black ink onto a sheet of paper. But how? Well, that part was up for debate. Using the imaging process, Cossairt and his team looked extensively at “Nativity” to figure out the master’s technique. What they saw were dark indentations that revealed bulges on the surface of the work — like someone had applied pressure from the back of the canvas to create microscopic ridges. That led to a new theory: Gauguin used a technique called monotyping. (Think: putting a piece of paper on an inkpad and then “drawing” on the surface facing you. The pressure from the paper pushing the opposite side into the ink creates an instant masterpiece.)

“We were able to verify that Gauguin used a monotype process for his prints by measuring the 3-D image of these shapes,” Cossairt says. But he also saw something else. “We were able to observe … all these broken lines.” Translation: Indents on the canvas that didn’t have corresponding ink on the other side. What was even odder was that these un-inked indents seemed to correspond to other Gauguin works. “The idea was that maybe the piece of paper that Gauguin used to start out ‘Nativity’ was on the bottom of a stack of paper,” Cossairt says. So just like when you write on a stack of sticky notes and leave indents on several layers of paper, “Nativity” bears the scars of other Gauguin works created before it.

For art historians like Joni Kinsey, a professor of art history at the University of Iowa, knowing that gets her and her colleagues one step closer to what they really want to know: the artists’ intent behind their work. Of course, a 3-D image doesn’t answer every question. In fact, as more works are analyzed, 3-D imaging might result in even more questions than answers. But for now, Kinsey sees possibilities in these new techie “wonders.”

“Those wonders are not in the digital technology; they are through the digital technology,” Kinsey says. “We need to use those as a springboard to engage with the world around us.”

Which is the whole point of art to begin with.