In mid-April, Carol Miller drove down the highway on the outskirts of Ankeny, Iowa, in her SUV. Edging past more than 100 acres of farmland, Miller admired her land. “I’ve been here since 1978,” Miller said. The land stretched into the distance, lying fallow. But it wouldn’t stay that way for long. Planting season was right around the corner and, by summer, the fields would be lush with crops — mainly corn and soybeans.

That’s what Miller was preparing for as she scouted the fields from the road. Once she and her husband had their crops in the ground, they would apply fertilizer to the fields. Fertilizers help boost crop growth so that farmers can keep up with the demand of the hungry world. But while these fertilizers do plenty of good, they contribute to a growing problem: nitrate pollution in the rivers and lakes.

Major bodies of water around the Midwest have become chock-full of nitrates. In summer 2013, the Des Moines and Raccoon rivers, which supply Des Moines’ drinking water, experienced the highest nitrate concentration in recorded history. Everyone’s first reaction was to point fingers at the farmers — the people pumping nitrogen fertilizers onto the farm fields. But the use of fertilizer is only a part of the issue and is not the main cause for contaminated rivers in the Midwest. Regardless of how nitrates reach streams and rivers, they are problematic to the health of humans and to the environment.

For starters, if consumed, these compounds can cause minor health problems in adults and severe health problems in babies. Not to mention that once this nitrate-concentrated water reaches the Gulf of Mexico, it deprives the ocean water of oxygen, killing off aquatic plants and animals.

To tackle this issue, the state of Iowa has devised a Nutrient Reduction Strategy. However, the nitrate problem has gone so far that it might take years and several other strategies to fix. To get things going, Des Moines Water Works sued three counties in northern Iowa whose farmlands use and release the most fertilizer into the water.

The Problem

It’s time for a science lesson. Promise it won’t take long. But it’s essential to understand why water has become a hot topic for discussion in the Midwest. The problem: nitrates.

Nitrates are odorless, colorless, tasteless compounds found naturally in the soil and groundwater. They’re one of several soil microorganisms. When microbes like bacteria, fungi, and protozoa break down organic material — stuff like dead plants, animals, and manure — they produce nitrate. Nitrates help make up protein and chlorophyll, the latter being necessary for photosynthesis, the process by which plants make their food. Without nitrates, the plant dies.

Everyone from industrial farmers to backyard gardeners uses nitrate-rich chemicals to fertilize their crops. These fertilizers supercharge the soil. Crops absorb these excess nitrates and turn them into chlorophyll — allowing them to convert more of the sun’s energy into food, which allows them to grow bigger, so they can suck up more nitrates … and the cycle is never-ending. The result? Larger, healthier plants with higher yields. Farmers who want to guarantee profits will definitely have nitrate-rich fertilizer as a part of their arsenal.

The problem is that typical summer crops like soybeans or corn can’t consume all the nitrates added to the soil during their four- to five-month lifecycle. This leads to runoff. “Nitrate is lost because the soil contains huge amounts of nitrogen, and if there is no growing plant to use that nitrogen, [the nitrate] is susceptible to loss to our water ways,” says Michael Castellano, assistant professor of agronomy at Iowa State University.

After corn and soybeans are harvested, soil lies fallow for months, which makes it subject to erosion. That’s particularly true if a farmer doesn’t practice methods to minimize such erosion. Nitrates in that exposed soil get washed away by the rain and snowmelt and flow into local streams, rivers, and lakes. They can also get left behind in the soil, where they eventually seep into groundwater. Either way, the problem isn’t that farmers are using too many nitrates in their fertilizer. If the soil was held in place by plants all year, there would be no runoff, and the plants would absorb most of the nitrogen that seeps into the ground and into our waterways — alleviating much of the problem.

Excess nitrates cause algae blooms in waterways. These blooms suck and steal the oxygen necessary for aquatic plants and animals to survive. This problem has become so pervasive that it has created giant dead zones in the Gulf of Mexico. Today, over 6,700 square miles of the Gulf is nearly devoid of life largely because of the nitrate runoff from farms in the Mississippi River Valley.

And it gets worse. Too much nitrate in our drinking water can become a danger to our health. According to the EPA, reported drinking water violations for nitrates have doubled in the last eight years.

For adults, drinking nitrate-contaminated water can cause headaches, dizziness, and difficulty breathing. But babies who are 6 months or younger really suffer the consequences. Nitrates deprive water of oxygen, and this lack of oxygen in water can turn a baby’s skin blue, because it makes it so hard for them to breathe. This scenario is more commonly known as Blue Baby Syndrome. It’s life threatening and requires an immediate trip to the hospital.

All this — simply because of bad water. The solution seems so easy, but it’s anything but. To truly understand this problem, it is necessary to look at what should have been done to prevent this problem years ago.

The Possible Solutions

For years, farmers have been blamed for dumping too much fertilizer into the soil, causing water pollution and other environmental problems.

What people forget is that farmers are no longer growing crops to feed their families — or towns — like they did half a century ago. An individual farmer reaches 155 people globally with his yields. “We have gone beyond feeding people in the United States and gone on to feeding people throughout the world,” Carol Miller says. Simply put: Farming is business. And just like every business, farmers want to feel their pockets jingling with money.

Fertilizers are not at the core of the Midwest’s water pollution problem. Exposed soil and soil erosion is. “The natural, organic soil in the nitrogen is about 10,000 pounds per acre, and that is quite a bit more than what we apply to our fields,” Miller says.

Like many farmers, the Millers use several methods to minimize soil erosion and fertilizer runoff. When planting, they disturb the soil as little as possible, a technique known as “minimum till.” After harvesting their corn, they leave the crop residue in the ground instead of plowing it under. They leave their soybean fields untouched after harvest. Doing so helps hold the soil in place over the winter. The Millers’ farm also employs terraces, which prevent erosion by flattening sloping terrain.

“Cutting fertilizer makes [only] about a 6 to 10 percent maximum improvement on water quality and reductions in nitrogen,” says Sara Carlson, research coordinator at Practical Farmers of Iowa. Carlson is a state representative for the Midwest Cover Crop Council, which focuses on finding ways to keep agricultural landscapes covered throughout the year to improve soil and water quality.

Cover crops — plants that grow during off seasons to keep soil from eroding — could be the solution. “Cover crops make a 30 percent improvement in water quality,” Carlson says. “A winter wheat crop that you would take for grain could make a 42 percent improvement in water quality, and a perennial crop can make a 72 percent improvement in water quality.”

Cash crops like corn, soybeans, and wheat are harvested in the fall. Winter transforms these once rich and ripe fields into a “no man’s land” for months, and this is where cover crops come in. “These crops reduce soil erosion and feed the microbes in the soil. There is a lot of life in the soil, and we know very little about it,” Carlson says. “But that life helps us cycle nutrients, builds soil, and helps us keep the soil in place. Just like we wouldn’t feed our cattle just four months out of the year, we need to feed our microbes more than just four months a year. We need to remember that there is life in the soil. It does a lot for us for free. Cover crop helps feed that soil life.”

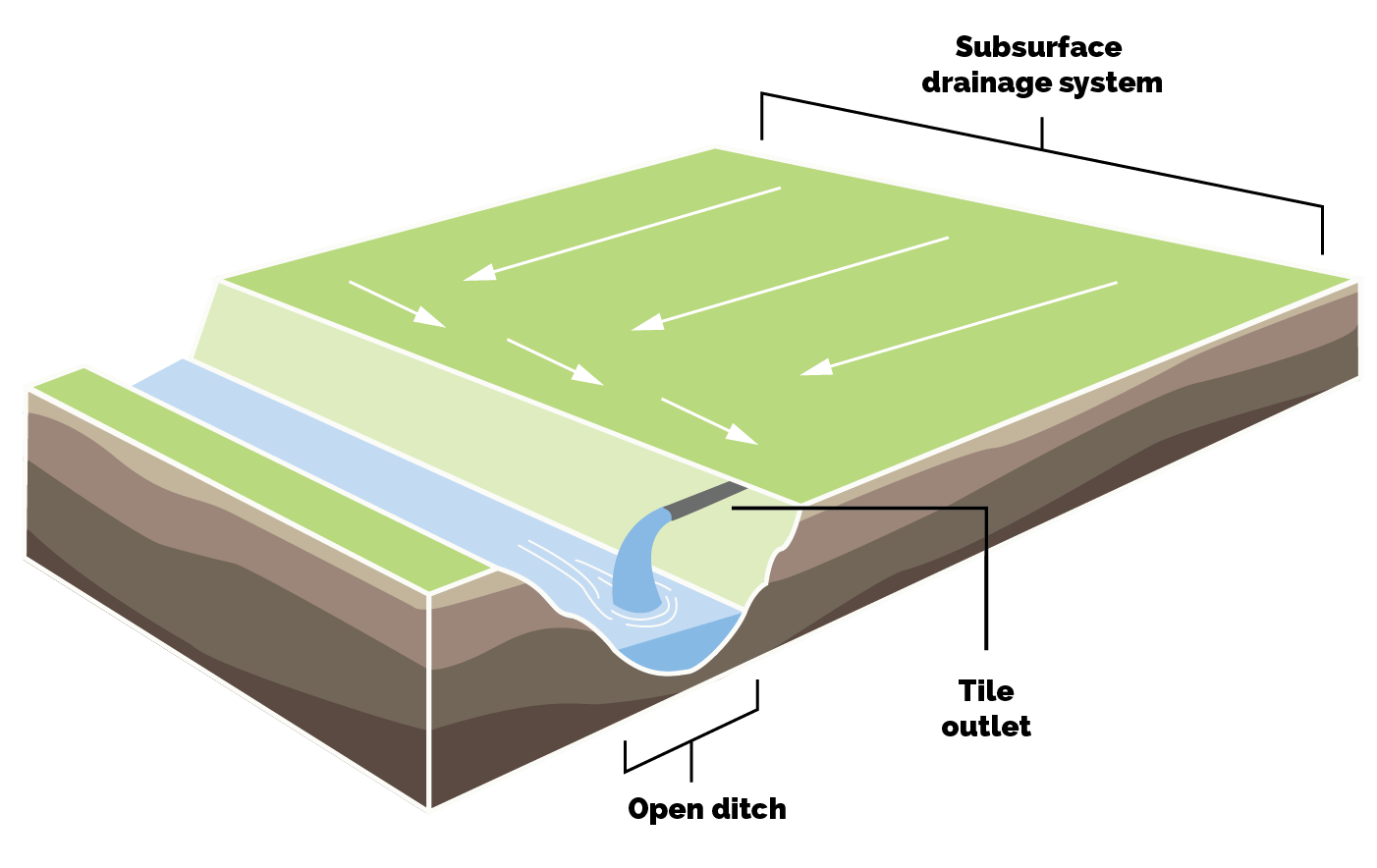

Different varieties of cover crops are planted and harvested in the off-season of regular crops. Some are planted in spring before a field crop, while others are planted in the late fall after field crops are harvested. Buckwheat, clover, oats, and peas are commonly used cover crops in the Midwest. These crops capture the nitrogen that would leave the farmland through drainage systems and get into major waterways.

“When we have rainfall and we have bare soil,” Carlson says, “we have a high chance of nitrogen and phosphorus leaving the system, and that causes downstream pollution.”

The Change-Makers

These health concerns, in tandem with the environmental consequences, are what prompted Des Moines Water Works to spend $4.1 million in 1991 to build a nitrate removal facility. The facility contains eight removal vessels, which use a process called ion exchange. This exchanges nitrate ions in the water for chlorine ions. It’s similar to the water filters we have at home. It’s just happening at a much larger scale and is focusing on extracting nitrates as opposed to magnesium and calcium.

These vessels have the potential to filter through about 10 million gallons of water a day. What happens to the nitrates? Believe it or not, the water utility discharges them back into the river. Once they extract all the nitrates from the water, the water is mixed in with partly treated water and put right back into the rivers. The nitrate removal facility helps provide us with clean drinking water, but does close to nothing when it comes to the environment.

The facility doesn’t run all the time — just when nitrates spike above the EPA’s maximum contamination level of 10 parts per million. For years, this has happened only in the summer, right after fertilizers have been spread over new crops and heavy rains have washed some of those nitrates downstream.

But last winter, from December 2014 to February 2015, the facility ran its nitrogen removal system for 97 days straight, an unprecedented run. “We don’t like nitrate concentrations, but we are used to seeing them in the summer, not in the winter and never at this length,” says Bill Stowe, CEO of Des Moines Water Works. In response, the Iowa Department of Agriculture devised the Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy. Participation by farmers is voluntary. The strategy is to educate farmers about conservation practices and show them new tools to improve water quality in the hope they’ll reduce nitrate pollution. “Our experience has been that that philosophy is ineffective,” Stowe says.

At $7,000 a day, the nitrate removal system costs a pretty penny. The expense is what pushed Water Works to sue the three northern Iowa counties — Sac, Buena Vista, and Calhoun, which are seen as major nitrate polluters. Water Works says tests in Sac County revealed groundwater nitrate levels of 39.2 parts per million, nearly four times the EPA limit.

“The interests of our consumers are not being currently recognized in the current political process and economic process,” Stowe says. “We believe we have rights that have been encroached upon by industrial agriculture in particular, and we are going to stand up for those rights.”

Des Moines Water Works serves about 500,000 people in the Des Moines area. Stowe says it’s the utility’s responsibility to ensure that the people it serves have access to safe drinking water.

Figuring out how to reduce nitrate levels — that’s a big cause for debate, one that often finds Stowe and farmers on opposite sides. “How do we ever get environmental conformity, environmental protection, if we let people off the hook for their environmental activities or economic activities?” Stowe says. “If you are a point-source polluter — if you are discharging an identifiable amount of waste into the waters of the state and the waters of the nation — you should be regulated.”

He has a point. Stowe says about 90 percent of the water problem can be attributed to agriculture. That may be true, but the use of fertilizer is not the core of the problem.

We know the problem. Why not solve it?

If cover crops are the solution to the nitrate problem, then why aren’t farmers planting them? Farming is dependent on Mother Nature. But money also comes into play. Farmers are unlikely to see a return on their investment in cover crops for up to eight years. The cheapest cover crop costs around $25 per acre, and farmers can own hundreds or thousands of acres.

“Most farmers are paying around $35 an acre to get a winter rye cover crop,” Carlson says.

Some research suggests that after four to five years, farmers might see an increase in yield of soybeans. Corn would be further out. It takes a lot of money and several years before farmers begin to see the benefits of nitrate reduction paying off.

There are around 80,000 to 90,000 farmers in Iowa. About 35,000 of them use cover crops. But Carlson says Iowa needs around 60,000 farmers to use cover crops to see a difference in water quality.

But cover crops aren’t always the solution. Cover crops work well in southern Iowa, Castellano says, but the same can’t be said about the north, given the weather and environment of that area. The Millers, for example, farm north of Interstate 80, where the climate can swing between drought and excessive rain or bring an early killing frost. That makes it difficult, if not impossible, for them to reliably grow cover crops.

Putting in saturated buffers — or rows of natural plants and trees that act as a buffer between the farmland and waterways — is a better option where cover crops aren’t feasible. “These processes take that nitrate and allow microbes to turn it into dinitrogen gas that we are surrounded by in the atmosphere every day and is totally innocuous,” Castellano says.

Who’s to Blame?

On one hand, Des Moines Water Works believes that farmers are solely responsible for these excess nitrates. But most farmers tend to disagree.

However, plenty of cities in Iowa do not have a nitrate removal facility. “The rural population has just not taken this seriously for a very long time,” Carlson says. “I don’t think it’s because they don’t want to. I am astounded that farmers aren’t realizing they are contributing to the problem.”

Several farmers who own flat farmland believe that they are not a part of the problem because they do not have soil erosion. This, however, is not entirely true. The riverbanks are covered in soil, so it would be incorrect to say that soil erosion is not occurring. Carlson says the agricultural industry — in conjunction with the organizations that support farmers and their decisions — has not realized that this really is a major problem. Which has led to farmers believing they aren’t actively contributing to the issue.

Miller is one of those farmers who has a strong desire to preserve the farmland and the river water. One of Miller’s farms is equipped with terraces that were put in place 40 years ago by the previous landowner. “We have maintained those terraces,” Miller says. “We have taken some trees and different growths off the terraces to help stabilize them, but for the purpose that they were built, they are doing very well.” Terraces are one of many ways to help reduce soil erosion and water runoff. Another of Miller’s farms has a tile drainage system in place, while another is equipped with buffer strips.

“Farmers are finding new ways to find conservation practices to segregate the nitrogen,” Miller says. “A long time ago, it was felt that if we preserved our farmland for the next generation and were good stewards of the land, that it would be beneficial not only to the family farmer, but to the people who get the food.”

And now, it’s not just about the food, but more so about being better stewards of the land. Our responsibility is no longer only to achieve the highest crop yields to feed the world. We also have a responsibility to everything that surrounds the process. That includes taking care of the soil and ensuring that our rivers remain clean for our safety along with that of aquatic plants and animals. But to decontaminate our waters is not going to be an easy job — the problem continues to grow and the clock is ticking.