The sky is usually black and lit up with lightning when Rance Hilton prepares for a job.

He’s kind of like a storm chaser, except he doesn’t get in his truck until after the rain stops. Because Hilton isn’t interested in the storm. He’s interested in the casualties the storms leave behind: trees. The sad-looking, contorted kind that still have plenty of trunk. Those are Hilton’s prizes. And if he can find enough of them, he might earn a couple thousand dollars. “I’m kind of a scavenger,” he says.

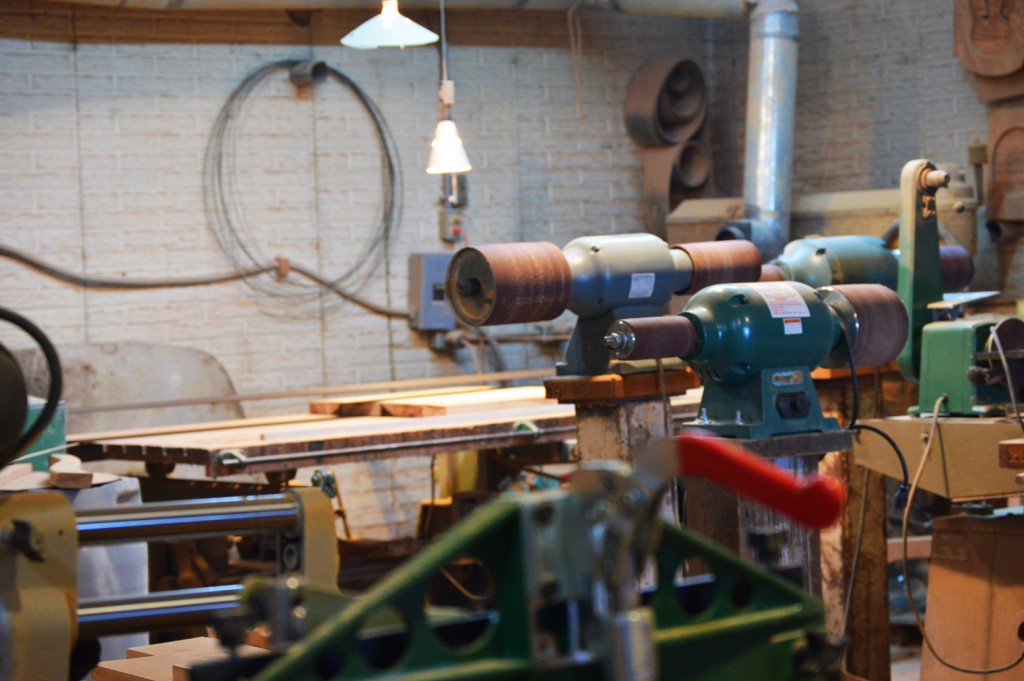

Hilton is a chair maker. He runs a one-man show out of his shop in Marengo, Iowa, a tiny town off a rural two-lane highway and a little over an hour west of Des Moines. And he’s a bit old-fashioned. In Hilton’s shop, the only piece of computerized machinery is his pocket calculator. Everything he does is by hand, using equipment manufactured before he was born. He slices thick boards of wood into curved armrests using a 1919 band saw, the blade protected by the inner tube of a 20-inch bicycle wheel. He sands the boards down on a 1930s stoke sander. Saws boards in half with a powerful 1950s circular saw that has no safety guard. And the wood: It’s all locally harvested — often thanks to a few generously windy storms. He has so much of it that his shed out back is literally sinking into the ground. “If I never went out and cut down another tree,” Hilton says, “I could probably still keep going for 10 years.”

The market might not let him. Today, the American furniture industry isn’t exactly in America. It’s been globalized, shipped off to Asia, where the wooden parts of a rocking chair may have been nailed together on an assembly line and then shipped back across the Pacific to be sold at your local Walmart. All for 30 percent less than it would have cost had it been manufactured here in the U.S. A report by Mann, Armistead, & Epperson, an international leader in furniture industry analysis, found that about three quarters of the current wooden furniture found on store shelves and in freshly furnished homes has been imported from overseas — the highest it’s ever been. Since 2000, employment in furniture manufacturing has fallen from roughly 680,000 to roughly 385,000. Furniture manufacturing plants in America have been closing left and right. And even the smaller, family-owned plants — like Hilton’s Amish neighbors several miles over in the Amana Colonies — are struggling to compete with Asia’s cheap, Walmart-friendly prices.

“It used to be that, if you would drive through the Amanas, it was stop-and-go traffic,” Hilton says. “You know, it would take you 10 minutes to go five blocks, just because it was so full of people. And now, it’s dead. You can whizz through town at 70 miles an hour.”

Which means that, to stay afloat, Hilton has had to take his chairs elsewhere: to festivals, the Iowa State Fair, and to woodworking competitions. That’s how he’s secured customers in every state but Hawaii. Passing through, they stop by Hilton’s booth and occasionally fall asleep in his rocking chairs by accident — “a good advertisement,” Hilton says.

He needs all the advertising he can get. He bought his shop in 2007 — the same year the Great Recession sent the housing market, and therefore the wood and furniture markets, into turmoil. He survived the downturn in the mass-market game by focusing on customization. “The thing I like to tell people is they’ll get what they want,” Hilton says, “rather than just going to a store and picking out what’s there.” He specializes in rocking chairs and a peculiar three-legged, bent-back chair, named for the smooth way in which the backrest curves into the armrests like a contorted horseshoe. He cuts all of these pieces with laser precision on his band saw and cuts them to accommodate any size. He can mix woods. He can engrave names on headrests — one time a customer requested “Old Fart.” “And I said, ‘Are you sure?’” Hilton says. “And he says, ‘Yep. Nobody else is going to sit in it.’”

But while customization is about the only segment of the American furniture industry that hasn’t been shipped away, it’s no fix-all. Jerry Epperson, who has watched the downfall of the furniture industry unfold over his 43-year career as an analyst with Mann, Armistead, & Epperson, says that, while the handmade heirlooms allow for a beautiful end product, the price point will deter the latest target group of buyers: Millennials. “They’re just getting started in their jobs and finishing their education, beginning to have their first homes,” Epperson says. “They can’t afford to buy custom furniture. They’re more likely to be buying inexpensive, more commodity-like furniture.”

Hilton’s rockers sell for $700 — far cheaper than the $1,200 average price, according to Epperson. For Hilton, though, and for many of his customers, price is beside the point. Some customizations are not for comfort or for aesthetic, but for memories. When storms knock down big backyard trees that held tire swings or tree houses, Hilton makes them into chairs so they can live in the living room like picture frames on a mantle. “They’ll never want to get rid of it, because it’s an heirloom to be passed down through generations,” Hilton says. “Their kids will get it, and their kids’ kids will get it. These chairs have a story to ‘em of their own.”

Hilton’s made a rocker for a family who, before selling a farm that had been theirs for 150 years, wanted to take one of their trees with them. For a man dying of cancer who wanted eight rockers made from his backyard walnut tree for his eight children. And once for himself.

When a storm with 110 mile an hour winds swept through his hometown of Dizert, Iowa, Hilton hopped in his truck the next morning, ready to scavenge. He drove past his boyhood home, and there were the two sycamores he used to climb — their tops wrecked by the wind. The trunks, though: enough for a few good chairs. Today, they’re rocking in his showroom — and have put several customers to sleep.